The Lost Frontier Fort

Eighteenth century Georgetown has a fascinating history which deserves to be known because it was a town that mattered. By eighteenth century standards, Georgetown was a sizable and significant place. Its position on the south side of the Ohio River placed it on the border of Indian country. It was a hub of early fur trade, a military site, and a supply depot for river travelers. Early settlers knew it was a gateway to the Northwest Territory at a time in our history when we were not quite civilized. Many immigrants had visited and passed through travelling to “the West”. In that migration and the later development of the American interior Georgetown played a significant role.

Professional historians have left generally untold the tale of the frontier fort in Georgetown, PA and its contribution to the defense of the western frontier. There are many references to the outpost in military correspondence, river traveler journals, and even in Meriwether Lewis’s journal of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Yet the fort has not been mentioned by any local historians including Bausman, Warner, Albert, and Agnew. [1] Only Thomas J Malone, an Ohio historian, has seriously researched the fort while preparing his biography of John Bever who was a pioneer surveyor and long time resident of Georgetown, PA. [2] Although there is no denial the fort existed, there is well known confusion surrounding the name of the outpost, the date the fort was built, and its precise location.

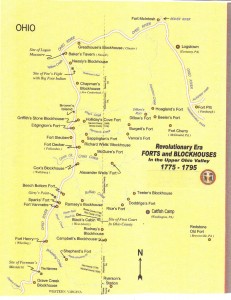

Map of Frontier Forts and Blockhouses (“Every Home a Fort, Every Man a Warrior”, Michael Edward Nogay, 2009)

Before investigating the specifics of the Georgetown frontier fort, a bit of background information is required to understand the differences between Revolutionary War era “public forts” and “family forts and blockhouses”. Continental or “regular” troops were stationed at public forts and supplied at public expense. Family or settler forts and blockhouses were not only local safe places of defense, but also the residence of one family in the neighborhood. Every frontier family belonged to a family blockhouse much like membership in a church. When an alarm was sounded families would “fort up” to their local safe house. Public forts usually had the word fort preceding its name: Fort Pitt, Fort McIntosh, Fort Henry, were all manned by regular troops and supplied by the government. Examples of family blockhouses were Vance’s Fort, Burgett’s Fort, Nessly’s Blockhouse, Baker’s Tavern. The word fort or blockhouse was added after the location name of settler forts. To my ears Fort Reardon’s Bottom has a poetic ring!

The importance of the Georgetown fort at the time when this section of the country was first settled may be inferred from military correspondence between 1777-1779. The following military orders and reports illustrate the variety of names and various spellings of the Georgetown frontier fort:

(1) Gen Edward Hand. In April 1777, Gen Edward Hand with Continental Army troops assumed command of Fort Pitt to organize the defense of the western frontier. To that date Fort Pitt had been manned by the Virginia militia. In addition to Fort Pitt, Gen Hand had under his command the fortified posts along the Ohio River which also included forts along the Allegheny River considered at that time an extension of the Ohio. The names of all but one of these forts are familiar to most high school students: Fort Armstrong (Kittanning), Holiday’s Cove (Weirton), Fort Henry (Wheeling), and Fort Randolph (Pt Pleasant). The one unknown post referenced in the military memoranda by General Hand was “Called Rordons Bottom about 40 miles below this post (Fort Pitt) an officer and 15 men.” This memorandum was dated June 3, 1777. [3] The location of this post was precisely in the place that would be named Georgetown, PA.

(2) Major Henry Taylor. On August 17, 1777 Major Henry Taylor marked the importance of the outpost at Georgetown by referring to it as “the Chief of the old posts”. It “was below Logs Town (Rochester, PA), I marched my men to this post… I then ordered the officers to meet at this post (Reardon’s Bottom)…”.

(3) Major Jasper Ewing. On July 25, 1778, Major Jasper Ewing while taking an inventory of the river forts reported one canoe “At Reardon’s Bottom“.

(4) Gen McIntosh. On January 11, 1779, Gen McIntosh from Fort Pitt wrote “On account of scarcity of our provisions I have kept… small parties of the 13th Virginia Regiment (Continental Army troops) at Rairdon’s Bottom…”. [4]

(5) Surveyor Christopher Hays. On Tuesday, 19 Nov 1782, Christopher Hays writing to General William Irvine on the progress of the survey of the western boundary of PA wrote “We … expect to strike the Ohio river about Thursday next between Fort McIntosh and Raredon’s Bottom.”

(6) Major Ebenezer Denny (later to become the first mayor of Pittsburgh). Major denning wrote in his journal during the time of Indian troubles, “The river continued to rise. With hard work we made it to Dawson’s (Georgetown), opposite the mouth of Little Beaver, about 8 o’clock at night.”

This military correspondence is ample evidence that a significant post had existed in Georgetown to provide a defense from frequent and continuous conflict with the Indians. Regular army troops were stationed at the blockhouse. That fact alone makes Georgetown a significant site. Rordons Bottom, Reardon’s Bottom, Rairdon’s Bottom, Raredon’s Bottom, or Dawson’s Ferry – by whatever name preferred - Generals Hand and McIntosh agreed the place was strategically important and stationed Continental Army troops there in 1777.

Fort Build Date. The date the fort was built is also elusive:

(1) According to Rev Bausman, “In 1786 Benoni Dawson built a “fort” on the site of Georgetown, and his son, Thomas Dawson, one on the other side of the river some years later. These were doubtless, as we have said, strong log cabins…” [5]

(2) Thomas J Malone wrote that “Dawson came from Maryland, to the vicinity of Georgetown in 1780 and built a fort in 1796 on the site of the town. These forts were doubtless strong log cabins.” In a Georgetown property transfer from Benoni Dawson Sr to John Bever on 31 Dec 1804 (Deed Book A P402-404), one phrase stated “an out lot of ground whereupon the said John Bever now has his mansion or dwelling on beginning at the northwest corner of the old blockhouse”. The term “old blockhouse” is telling in 1804. If the old blockhouse had been built in 1796, it would only be eight years. Eight was not old even in 1804.

(3) In John Reardon’s application for a Revolutionary War pension dated 7 Sep 1833 listed his service from 1 Mar 1776 to 31 Oct 1776. During that time, John Reardon was stationed on the Ohio River building blockhouses. He arrived in Georgetown in the 1760′s. No doubt he probably built a blockhouse in Georgetown before 1786 or 1796.

(4) Local tradition, Georgetown folklore widely believed yet unsubstantiated, claimed that the fort was constructed by the French as early as 1760. Although there are no records to prove it, it is as good a date as any. The French began to erect a line of forts for the purpose of connecting Canada with the Mississippi valley as early as 1719. [6] According to Bausman, French traders were thought to have been on the Ohio as early as 1720. English traders were not far behind arriving around 1730. [7] French explorer Gaspard de Lery in June 1739 mentioned in his journal the Indian petroglyphs directly opposite Georgetown. [8] The governor of New France in 1749 sent out an expedition led by Piierre Joseph Celeron for the purpose of depositing medals (lead plates) at “important places” to advance France’s claims on the Ohio River valley. One medal was found in Venango, PA. [9] A similar medal was found in Pt Pleasant. [10]

In the late 1760′s, Col Bouquet was actively building forts in the northwest region of PA between Erie and Pittsburgh. As early as 17 Apr 1770, George H Loskiel in his History of the Moravian Mission gave a detailed account “of this settlement” (Georgetown) after canoeing to the mouth of the Beaver Creek “which they entered and proceeded up to the falls”. They met with David Zeisberger who delivered a “copious speech”.. In 1772 David Zeisberger and John Hechewellder founded the Moravian Christian Mission at Schoenbrunn, Tuscarora County, Ohio. The missionaries crossed the river at Georgetown and followed the Indian trail to their central Ohio mission settlements. The early Moravian missionaries lend support to the idea that the settlement of Georgetown took place by 1770. So, the fort was probably erected between 1770 and 1777.

The “settler forts” on the southside of the Ohio River were nearly all erected during the terror and panic of 1774. The settlers in the Georgetown vicinity were rightfully alarmed because they knew that the Indians would make war in revenge of the murders at Baker’s Tavern. The Greathouse Party Massacre took place on 30 Apr 1774 approximately six miles by water from Georgetown. The settler forts continued to be used through a long series of Indian wars and alarms, most frequent and serious from 1778-1783, until a lasting peace was won by Gen Wayne’s victory in 1794. It is not beyond reason to believe that the “Chief of the old posts”, in Major Henry Taylor’s words, was built before the settler forts in 1774 or even earlier by the French. By 1777, it was manned by the Continental Army.

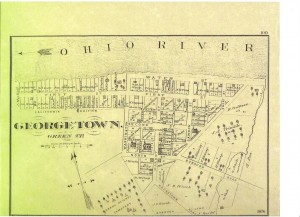

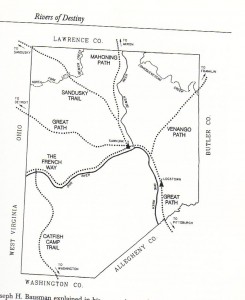

The most contested of the three issues of the forgotten fort was its location. To understand the different positions of the various historians who have weighed in on the subject, a geographic description of Georgetown is required. Safe from floods on a bluff ninety feet above the river level, the three mile flat bottomed land of Georgetown was bounded by softly swelling hills and enclosed by two small streams: Mill Creek and Smith or Nash Run. The courses of both streams have been modified by sand digging operations so today their mouths are not what I remembered as a child. Mill Creek, nearer its source, supported a grist mill. Flatboats and keelboats built in Georgetown were launched from Nash Run. Nash Run had a saw mill and probably a distillery, or “still house”, on its banks. Converting grain to whiskey was not an uncommon practice during this period when the market for grain was low and the demand for whiskey was high. Neither Mill Creek nor Nash Run was comparable, in volume or power, to Beaver Creek which emptied into the Ohio opposite Georgetown in Indian country. Georgetown, the terminal point on the Catfish Camp Trail and across the Ohio River from a trail connecting to the Tuscarora Path, was an ideal site for a frontier fort. Crossing the river at Georgetown and following the Beaver Creek which intersects the Tuscarora Trail and the Great Path saved many days of travel for early settlers. The Tuscarora Trail goes into the Northwest Territory to the Moravian missionary villages.

Indian Trails in Beaver Co PA (“Rivers of Destiny”, pg 99)

Travel by water was much faster, and less expensive, than by land. Boats floating with the river current at ten to twelve miles per hour were much faster tha ox carts. Of course, roads did not exist. Indian trails were narrow and rough – single person passage. So it makes sense that early settlers would use the river to get to Georgetown, cross the river on Dawson’s Ferry, follow Beaver Creek to the Tuscarora Trail to central Ohio rather than take longer route to Pittsburgh and from there an overland route from Beaver, PA or Rochester, PA via cart or wagon. Later the Catfish Camp Trail became known as the Washington Post Rd. Militia from the Burgettstown area used this trail and Dawson’s ferry to join Mad Anthony Wayne’s army in 1794.

Most local historians of Beaver County argue that the site of the Georgetown fort was on the south bank of the Ohio either at the mouth of Mill Creek or Nash Run. Because of the word “Bottom” they believe the fort had to be along the river at the mouth of a stream. There is no physical evidence to support their theories. Equally likely, the name, Reardon’s Bottom, was given to the entire plain along the river. It must also be noted that none of the military correspondence mentioned the mouth of a creek at Reardon’s Bottom regardless of the spelling. The word bottom should not be misinterpreted. For comparison, Mingo’s Bottom contains about 200 acres of land.

Deed Book A P402-404 again reveals much information about the location. The “out lot of ground” on which the “old blockhouse” stood was adjacent to Lots 1 and 2 of the original town plat. It is precisely the location of the home formerly owned by Anna L and John F Nash and currently owned by Judith and Nicholas Maravich.

Georgetown folklore, widely believed and well substantiated, claimed the forgotten fort is the “blockhouse” on Lot No 11 as the town was laid out by John Bever. [11]

In 1792, James Clark, one of the first settlers on the north side of the Ohio River, was ambushed and killed by Indians. Hearing the attack, his wife took a canoe and her child across the river to the blockhouse in Georgetown. She did not paddle the canoe one mile downstream to Reardon’s Bottom at the mouth of Mill Creek nor did she paddle upriver one half mile to Reardon’s Bottom at the mouth Smith (Nash) Run. [12] She escaped to the blockhouse in Georgetown. This attack was two years before the end of Indian hostilities in western PA.

Whether the old blockhouse still stood was always a question asked at Georgetown family reunions. People at these reunions, such as the Kinsey Reunion in 1908, were only two generations distance from the people who manned the fort during Indian raids of the frontier days. Their memories of the fort along with family stories pointed to the “blockhouse” on Lot No 11 as the location of the frontier fort.

Ohio historian, Thomas J Malone, was the only historian to examine and measure the home at Lot No 11. His first of several visits was on 14 Sep 1967. His conclusion ― “it is the blockhouse”. [13] “The original house was made of logs, two stories high, walls 17 inches thick, inside measurement 16×16 feet with puncheon floors and the ceiling not over seven feet high.” [14] These characteristics were similar to other frontier forts. Fort Burd (Redstone) in Brownsville, PA was 39 feet square; the Presque Isle Blockhouse was 56 feet square and 20 feet high; Fort Steuben was 25 feet square and 11 feet high (1 1/2 stories) and could quarter 14 men. [15] Coincidentally, Thomas J Malone’s research identified the property as the “mansion” of John Bever who ran a tavern from the property. In 1803 George Henry Loskiel, a Moravian missionary, bound for Goshen, OH, penned a long poem about his trip while stopped at John Bever’s tavern. [16]

The lost fort of Georgetown a is prisoner of history – a town half remembered; a town of many aliases; a town that confused early historians. The existence of the fort and its occupation by Continental troops are a matter of history now, but there are many details about the fort that have never been written. There is considerable evidence that the frontier fort exists in a currently standing home. Its second story was removed in the early 1900′s, but the hand-hewn logs forming the walls and its stone foundation can still be observed. The people of Georgetown in the late 1800′s and early 1900′s believed this home was the fort. Dismissal of this evidence by saying that “local tradition has a tendency to imagine many events as earlier than they actually occurred” underestimates the value of local traditions and oral history. [17] Legend and reality are often not so far apart.

The roots of Georgetown are deep despite the lack of recorded facts concerning The Lost Frontier Fort.

References.

[1] Denver and Eugenia Walton and Bob Bauder, Rivers of Destiny, Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation for the Beaver County Bicentennial, 1999, p 58.

[2] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 31.

[3] Denver and Eugenia Walton and Bob Bauder, Rivers of Destiny, Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation for the Beaver County Bicentennial, 1999, p 58.

[4] Denver and Eugenia Walton and Bob Bauder, Rivers of Destiny, Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation for the Beaver County Bicentennial, 1999, p 58-59.

[5] Rev Joseph H Bausman, The History of Beaver County Pennsylvania and Its Centennial Celebration,(The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1904), p 170-171.

[6] Gentleman of the Bar, Western PA and of the west, WO Hickel, Harrisburg, 1850, p 30.

[7] Rev Joseph H Bausman, The History of Beaver County Pennsylvania and Its Centennial Celebration,(The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1904), p 170-171.

[8] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 4.

[9] Gentleman of the Bar, Western PA and of the west, WO Hickel, Harrisburg, 1850, p 35.

[10] Gentleman of the Bar, Western PA and of the west, WO Hickel, Harrisburg, 1850, p 36.

[11] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 29.

[12] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 4.

[13] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 31.

[14] Ibid.

[15] www.profsurv.com/magazine/article.aspx?i=70281

[16] Thomas J Malone, John Bever, Pioneer Surveyor, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1975, p 30.

[17] Denver and Eugenia Walton and Bob Bauder, Rivers of Destiny, Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation for the Beaver County Bicentennial, 1999, p 60.

Copyright © 2010 Francis W Nash

All Rights Reserved