Steamer Biographies

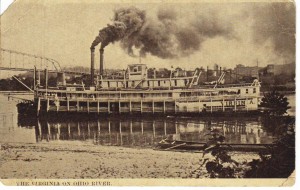

The American inland river steamboat, gleaming with romance, is one of our most valuable heritages. The light draft vessel was the technological wonder of its day providing access to the western territories decades before the arrival of the railroads. That many Americans continue to be fascinated by the historical exploits and romantic spirit of steamboats is completely understandable.

The thought of a sternwheel packet churning through the water with its tall stacks spewing local thunderclouds and raining sparks while its whistle warning of its approach puts us on the beam. By definition, a packet was a vessel that transported both freight and passengers. Some packets were faster but not so reliable; some were larger but also slower; some were more luxurious, but carried less freight. They had the grace of swans on a highway which cost nothing to build.

In the golden age of steamboats, fast boats attracted more passengers and better rates for cargo. Americans of the time were obsessed with speed, as they are today. The boat that held the honor of fastest time on a trade route was awarded a mount of gilded antlers which was proudly strung between the tall stacks of the boat or mounted in the pilot house. In May 1850, the Buckeye State made its fast run on the Cincinnati to Pittsburgh trade route – 468 miles in 43 hours – a record unmatched by any steamboat.

Contrary to popular belief, steamboats carried more troops and freight during the Civil War than their latecomer competitor – railroads. Railroads were unreliable much of the time near the war fronts. Rivers could not be blown up. The demand for steamboats was so great that all available vessels included aged boats were pressed into service. After the war, the riverboat trade never recovered. Their glory had passed to the land – steam railroads.

The Management of a Steamboat.

The crew. Steamboat crews on an average size sternwheeler numbered about 50 persons. The officers were: one captain, two clerks, two pilots, two engineers, two mates (boatswains), and one steward. The crew numbered one head cook and two assistants, one hostellier (barkeep), seven cabin boys or 6 chambermaids and one laundress, one porter, one barber, four firemen and 20-30 deckhands.[1]

Duties of the officers. The captain often came through the ranks with a record as a mate, clerk, and pilot. Although the captain was first in command, under some conditions, he was subordinate to the pilot by law. His attention was directed to the overall management of the boat as a business enterprise. As an officer, the tasks requiring the greatest skill and knowledge were divided between the pilot and engineer. The pilot had navigational command while at the wheel and absolute authority. The engineer was responsible for the operation and safety of the steam engines. The chief clerk was a human calculator. The mate directed the deck hands often by dominating the men with curses and brute intimidation.

Steamboat Design.

For the inland rivers, steamboats were designed with extreme length and shallow draft. When the boilers were installed in the front and the engines in the rear, the boat tended to droop in the bow and stern and rise in the center. This effect was called “hogging”. To rectify this condition, the hog chain system was developed. The system was a series of long iron rods held up by wooden braces attached to the bottom of the hull. Tension was applied to the chains to straighten the hull with turnbuckles. Adjustments were made when needed. The science of packet building had made great progress.

Missouri River Steamboats.

The Missouri River steamers were a breed to themselves. These vessels were not the nodding slower than an island deep water boats of the lower Mississippi River. The average Missouri River packet was a sternwheeler 165 feet long not including the wheel. It was 30 feet wide and its draft was about 4 feet when loaded and 20 inches empty. The weight of the boat was close to 300 tons and its capacity was between 200-300 tons. Most “mountain boats” had two decks with the pilot house on top although some had a Texas deck with luxurious cabin space. [2]

One of the finest mountain boats, the Nick Wall, built in 1869, was 180x33x5 and rated at 338 tons. [3] The Nick Wall also had a Texas deck to accommodate cabin passengers in the style expected of a luxurious packet.

Steamboat Machinery.

Engines. All steamboats had two engines. Sidewheelers had one engine to drive each wheel independently. Sternwheelers had two engines installed on each side of the boat working together to drive the rear wheel. The single piston engines were rated by the inside diameter of the piston and the length of the stroke. For example, 18’s by 6 translated to an 18 inch diameter of the piston and a 6 foot length of movement of the piston in the cylinder. The engines were connected to the crank pin on the wheel by a long arm called a pitman.

Boilers. The boilers were long, cylindrical, and small in diameter. Installed in batteries of two, some large boats had up to eight. The size of a boat was described by the number of boilers installed. Without reference to the length of breadth of beam, a riverman would described a vessel as “a two boiler boat” or “a four boiler boat”. Overhead the boilers were connected by a steam drum and underneath by a mud drum. The fire circulated over the firebox and up the tall stacks. The engines required high pressure. If sediment in the water became encrusted in the boiler or if the boilers were pushed to their limit for racing, they could easily blow. The most frightful danger of a deck passenger was an exploding boiler that would scald or kill everyone nearby.

Tonnage Measurement. In 1789 Congress passed an act requiring import duties based on vessel tonnage. The formula developed was:

[(L x 3/5B) x (B ½ D)] / 95

L= length of beam

B= beam on main deck

D= depth of hold

Cost of operation.

Expenses. The cost of operation exclusive of wood was approximately $150 per day. Burned at a rate of one cord per mile on the Missouri, the average expense for wood was $100 per day. The total operational cost per day was $250. To cover the expenses and realize a profit, the freight charges were about ten cents per pound. The initial construction cost of an average sized steamer was $10,000 to $12,000. [4]

Profits. A trip from St Louis to Ft Benton was approximately 60 days up river and 15 days on the return. The total cost of operation at $250 per day was $18,750. Assuming 200 tons of freight at ten cents per pound, the gross receipts for freight would be $40,000. The difference was profit. In 2007 dollars the profits would be between $300,000 and $540,000 depending upon the inflation calculator used.

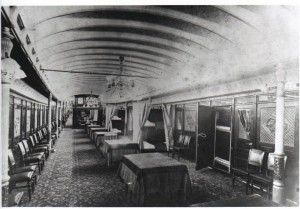

In addition to freight, packets carried two classes of passengers. The most luxurious class was a cabin rate; the other mode of travel was a deck passenger. The cabin rate between St Louis and Ft Benton in 1869 was $150 and included a berth and meals served in the main hall of the cabin area. The deck rate of $35 included no food and no berth. A deck passenger slept on deck with the crew and provided his own nourishment and generally helped when the boat was wooding up, sparring, and doing other manual work.

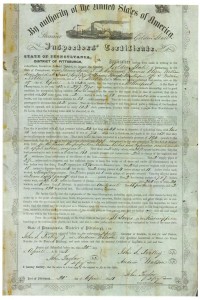

License Certification. The issuance and revocation of steamboat licenses was controlled by the Steamboat-Inspection Service whichwas established by the Steamboat Act of Aug 30, 1852. On Aug 30 1852, licenses were required for all steam vessels. Every vessel was required to post a certificate of inspection valid for 12 months. The 1871 Act added masters and chief mates to the list of steam vessel officer’s licenses. After an amendment in 1891, the licenses were issued for five years and renewal was at any time before expiration.

Georgetown Steamer List.

The steamers listed in the table that follows were owned and operated by to Georgetown rivermen from 1837-1906. Due to a few inconsistencies, the packets have two build dates from two different sources: Captain Frederick Ways Jr’s “Packet Directory 1848-1994” and a centennial history of Allegheny County – “Allegheny County’s Hundred Years” by George H Thurston. I have also identified the majority owner of the boat where possible. The ownership of most to Georgetown packets were shared between several parties. For example the original ownership of the steamer Clara Poe, was divided as follows:

Str Clara Poe – Initial Cert of Enrollment from the Port of Pittsburgh

| Owners and Partners | Share | Vol: | 6642 |

| Jacob Poe | 1/4 | Enroll No : | 182 |

| Thomas Poe | 1/8 | Cert Date: | 26 Nov 1859 |

| Martin L Poe | 1/8 | Cert Type:: | Admeasurement 11 |

| George Poe | 1/8 | Build Locn: | California, PA |

| Build Date: | 1859 | ||

| Jonathan Kinsey | 1/8 | Master | Thomas Poe |

| George W Ebbert | 1/8 |

In the steamer table I have declared Thomas W Poe the prime owner of the Clara Poe because he did own a share iequal to his brother Jacob Poe in later enrollment entries. But Thomas had more at risk because he was the master of the packet named in honor of his daughter Clarissa. The initial entry was short 1/8 share. In the second entry and later entries brother Andrew Poe is listed as a partner with 1/8 ownership.

Most Poe family boats were not large for their day. The Poe brothers believed that moderately sized boats yielded a better return on their investment. Costing less and shallow enough in draft because of their size, Poe boats could run, especially on the upper Ohio and Missouri Rivers, when the river level was too low for larger craft to operate. They could make more paying trips per season than owners of larger boats. The Poe brothers also favored the sternwheel design for their packets. In theory, the sternwheel design had much to recommend it notwithstanding their light draft. Designed for the Missouri River, the Poe light draft “mountain boats” found abundant opportunities on the Mississippi River when cold weather put an end to navigation on other northern rivers. When regular packets were out of commision due to the low stage of the Mississippi, freight rates would rise for transporting flour and other merchandise to New Orleans and other southern ports. This business model made sense and proved its worth by returning good profits over the years.

The str Horizon was another Georgetown “family boat”. Her owners were John N Mc Curdy (1/3), Thomas S Calhoon (1/3), Richard Calhoon (1/4), and William White (1/12). The Horizon officers were Richard Calhoon (master), Thomas Calhoon (clerk), Joseph Calhoon (steward), William H Briggs who had married JT Stockdale’s sister (engineer), and James Mackall (mate).

The ownership of other Poe boats and Stockdale and Calhoon partnerships was equally complex. In the table blow the “Initial Owner” column, the named riverman, controlled a major share of the packet and/or was the driver of the boat.

Each research trip to The National Archives uncovers more information. The steamer list is in alphabetical order by packet name. It can also be searched and sorted Build Date and Build Location, Primary Owner and Build Date, etc., leading to interesting analysis.

Summary.

Steamboats were admired for their luxury, their comfort, their ornamentation – in a word – their style.

References.

[1] John G Lepley, Packets to Paradise Steamboating to Fort Benton, (River & Plains Society, 2001), p 80.

[2] John G Lepley, Packets to Paradise Steamboating to Fort Benton, (River & Plains Society, 2001), p 81.

[3] Frederick Way, Jr.,Way’s Packet Directory, 1848-1994, (Ohio University Press, Athens 1994), p. 347-348.

[4] [4] John G Lepley, Packets to Paradise Steamboating to Fort Benton, (River & Plains Society, 2001), p 80.

Copyright © 2018 Francis W Nash

All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be reproduced without permission in writing from the author.