Civil War Transports

During the Civil War, the Union Army through the Army Quartermaster employed a large number of steamboats on the western rivers. The government owned ninety-one (91) steamers. [1] Many hundreds of other vessels were employed either under temporary impressment or charter to the Quartermaster. These boats served as a primary element of the Army supply system transporting supplies and troops. A few were even modified and used in direct tactical operations as tinclads.

Background. Transportation of soldiers and supplies was not performed exclusively by railroads, steamboats, or horses and wagons. The three major types of transportation were often used in conjunction with one another. “During the Civil War railroads were well organized companies. Unlike the railroads, the administration of a steamboat company seldom consisted of more than a few members and one boat. For large movements of troops and supplies, the transportation offices of the Army had to manage many small charters or contracts with steamboat men. It was possible to make railroads wait for their money, but steamboat men had to be paid directly. These perplexing problems led the Army, and Congress, to favor working with the railroad barons even though the cost was much greater.”[2] That same attitude is partly the reason that historians have paid so little attention to steamboat transports. When they have described the role played by the transportation systems in the Civil War, most of their studies have been devoted to railroads and the great railroad barons.

However, it was not by chance that the Union Army followed the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and their tributaries. These rivers were military highways. And what roads they were – with the Tennessee and the Cumberland Rivers running for hundreds of miles through the central part of the Confederacy. The immense superiority of the North measured in gunboats and packets turned the tide against the Confederacy in the west. These floating fortresses could move an army in two or three hours longer distances than a regular army could march in a day. This combination of power with speed could not be matched by the South. This advantage was also due in part to the fact that railroads in the South were undeveloped when compared to those in the North.

In the 1860′s, nothing could equal a river as a supply route. A river could not be blown up. But due to the natural unpredictability of a river that lifeline was not always available. Military opinions on railroads and steamboats were mixed. Describing his aversion to the Tennessee River, Col Richard D Cutts wrote “The railroad to Memphis and Columbus will be open next week & the Tennessee River may then go to hell where water is most needed.” [3] General William Tecumseh Sherman expressed the antithesis in his fear of reliance on a railroad, writing ” … I am never easy with a railroad which takes a whole Army to guard, each foot of rail being essential to the whole; whereas they can’t stop the Tennessee and each boat can make its own game.”[4]

Military control of civilian steamboats presented significant problems for the civilian owners. That subject, Army control of civilian transports and civilian crews, was evaluated extensively by Francis H Upton in 1861. [5] Employed directly as carriers for the military, these civilian vessels “would become legal ships of war” and the civilian crew, “though not enlisted soldiers, are to be subject to orders, according to the rules and discipline of war.”[6]

Arming the impressed and charted vessels was one of the many problems for the civilian owners. If not a universal practice, arming civilian transports on the western rivers was widespread. However, some uncertainty exists around who manned the weaponry. In general, the Army did not hesitate to use civilian crew members as combat personnel. The boat was under military control. And the entire crew was under military discipline. Translating that means a civilian crew member would be subject to, in accordance to military discipline, a court martial or lashing depending on the offense. As civilians, they were not entitled to pensions, yet the crew were subject to the same harsh treatment as prisoners of war if captured. [7] The result was continuous friction between the soldiers and civilians serving together. For the naval officers commanding the requisitioned steamers, there was often “too much steamboat and too little man-of-war”, and that was that.

The Army Quartermaster also used its authority quite freely to discipline and intimidate pilots and engineers. The Quartermaster overruled the civilian regulatory authorities to license and revoke the licenses of civilian pilots and engineers. To prevent collective bargaining over wage rates Col Lewis B Parsons issued and order in 1862 that read “… if anywhere on the Mississippi… if a pilot demanded wages exceeding $200 per month, he was to immediately have his pilot ‘s license revoked.” [8] Not only would the offending pilot lose his civilian job, he would be subject to the draft in his home state. The work of the steamboat men was dangerous while their pay, if any, was reduced to well below the commercial rates before the war.

Personal property loss was also severely controlled by the Army for impressed and chartered transports. The captain or owner could file a Petition of Indemnity. The paperwork was burdensome in wartime and compensation was subjective because “the government assumed no responsibility if a boat was lost due to normal risks of nature (snags) but only if the loss was due to direct enemy action”. [9] Direct enemy action was an euphemism often used to deny compensation. The government also did not renumerate the boat owners for fuel in many of the charters.

All in all the war was not an economic benefit for the owners of inland river steamboats. Many of the independent owner/operators never recovered from the financial hardships caused by the war even though they supported the Union cause. These hardy steamboat men took the hard knocks but without the glory.

Georgetown and the Civil War. Georgetown steamboat men played a prominent role in the Civil War. With a population never exceeding 297 according to the US Census records, Georgetown is a classic small town with a big history. All of the steamboat captains and pilots from Georgetown served the Union cause. According to the US Census of 1860, 38 Georgetown men were employed on steamboats: nine captains, six pilots, three engineers, three clerks, five mates, four stewards, four cooks, three mechanics, and one deck hand. While their fathers commanded boats on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, the younger Georgetown men were searching for a different kind of adventure and glory. Eleven Poes from Georgetown served in various regiments of PA or OH Volunteer Infantry. That represented 16% of the Georgetown population, and this total does not include other old family named men from Georgetown or men from Greene Township surrounding Georgetown borough.

The following table lists the boats owned and/or operated by Georgetown captains during the Civil War. Three met tragic ends during the conflict.

Civil War Transports

| Steamer | Owner/Capt | Listed byWay | Listed by Gibsons | Listed at Shiloh |

| Argyle | Jacob Poe |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Citizen | Richard Calhoon |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Clara Poe | Thomas W Poe |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Ella | Adam Poe |

Y |

Y |

Chartered |

| Horizon | Thomas S Calhoon |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| JT Stockdale | JT Stockdale |

Y |

Y |

? |

| Jacob Poe | Jacob Poe |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Kenton | George W Ebert |

Y |

Y |

Chartered |

| Leonora | Richard Calhoon |

Y |

Y |

Chartered |

| Lizzie Martin | Thomas S Calhoon |

Y |

Y |

N |

| Melnotte | Richard Calhoon |

Y |

Y |

N |

| Neptune | Adam Poe |

Y |

Y |

? |

|

|

|

|

Note 1: Red font implies lost – whether burned or sunk.

Note 2: Chartered implies the boat was in service but not at Shiloh.

Of the nine boats identified, only the str Argyle was a side wheeler (SW). It was built in Freedom in 1853. The sternwheel design, favored by the Georgetown steamboat men for several reasons, was far better in shallow water. The wheel suffered less damage from floating debris. The boat was trim, more powerful and had a lower draft so that it could venture into water forbidden the sidewheeler. The sternwheel design was a definite advantage on tributaries of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, such as the White, Tennessee, and Cumberland. SWs were good in big water like the Ohio and Mississippi and they were more maneuverable because the wheels could rotate in opposite directions―peerless for spinning doughnuts in deep water. However, in rivers like the Cumberland and Tennessee, sternwheeled medium sized vessels were superior.

The Citizen was built in Elizabeth, PA in 1860.

The Clara Poe was built in California, PA in 1859.

The Ella was built in Elizabeth in 1854;

The Horizon in Freedom, PA in 1855;

The JT Stockdale was built in West Brownsville, PA in 1863. (It was purchased by the US government and converted into tinclad #42.)

The Jacob Poe in Shousetown in, PA in 1862;

The Kenton in Shousetown in 1861;

The Leonora in WV in 1861;

The Lizzie Martin in Belle Vernon, PA in 1857;

The Melnotte in California, PA in 1856;

The Neptune in California in 1857.

Not all the Georgetown steamers have recoverable Civil War histories. Nor were all the boats owned and operated by Georgetown men for the duration of the war. Several boats were sold before their Civil War exploits unfolded. My focus will be on my ancestors steamers the Clara Poe and the Kenton.

Str Clara Poe. The str Clara Poe was named after Thomas W Poe’s oldest daughter, Clarissa. Her departure from the Monongahela Wharf loaded with soldiers was vividly recorded on 18 Oct 1861. The following details were from a history of the 78Th PA Volunteer Infantry.

“The 78th PA Infantry boarded “on Captain Thomas Poe’s Clara Poe… At 6:00 PM ropes were released, whistles sounded, anchors weighed, and the Clara Poe… sailed quickly from the Monongahela River into the Ohio River enroute to their jump-off point of Louisville, Kentucky, some three days away.”

That Oct day was the beginning of the Civil War for my Georgetown captains. With great fanfare and expectations of a short war, the 78th PA Voluntary Infantry enlistments were for 90 days.

The next reference to the str Clara Poe was a mercy mission.

Pittsburgh, PA,

Feb 19th, 1862

I desire that the captains of the following

steamers be placed on record for the patriotic

and liberal (volunteering) of their services and

boats, without renumeration, to proceed

immediately to the Cumberland River to

relieve the sick and wounded soldiers:

Rocket, Capt Wolf; Clara Poe, Capt Poe,

Horizon, Capt Stockdale; Emma, Capt

Maratta; Westmorland, Capt Evans;

Sir William Wallace, Capt Hugh

Campbell.

B. C. Sawyer, Jr., Mayor[10]

The mayor of Pittsburgh acknowledged that these captains with their boats, without pay, steamed to Tennessee to transport wounded and sick soldiers back to Louisville and St Louis. Three of these six boats were later destroyed during the war: str Clara Poe, str Horizon, and str Emma.

Packet owners shared their risk. This chart is the original ownership of the str Clara Poe . Note that ownership does not venture outside the family and close friends. Jonathan Kinsey was a pilot and neighbor of Jacob Poe. George W Ebert was a brother-in-law married to Nancy Ann Poe. All of the Poe vessels were “family” boats meaning that their ownership was shared among several family members and close friends.

Str Clara Poe

| Owners and Partners | Share |

| Jacob Poe | 1/4 |

| Thomas Poe | 1/8 |

| Marin L Poe | 1/8 |

| George Poe | 1/8 |

| Jonathan Kinsey | 1/8 |

| George W Ebbert | 1/8 |

per Capt Frederick Way, Jr

Not all transport missions lacked excitement. There was potential danger round every bend. The following New York times article exposes the problematic and dangerous conditions that supply transports encountered. This risky life forced captains and pilots to be cunning and crafty or victims of the war.

“On Saturday noon of the last week (Sat Aug 06 or 13, 1864) the Clara Poe, bound for the Tennessee River with two heavy barges loaded with government stores, having on her own deck a load of fat cattle was attacked by a rebel force estimated at 700. The rebel commander Johnson ordered the Clara Poe to bring to, and upon her Captain refusing to comply. a fire of musketry was poured upon her.” The article goes on to state that the Clara Poe had been pierced with approximately 500 musket bullets.

NYT Aug 15, 1864

The article goes on to state that the str Clara Poe had been pierced with approximately 500 musket bullets. It goes into great detail about the escape – discarding the barges, running the cattle off the deck into the river, etc. A good read. [11]

The final documented charter for the str Clara Poe extended from 30 Dec 1864 to 22 Jan 1865. In Jan 1865, 52 steamboats including the Clara Poe chartered by the Army Quartermaster moved Schofield’s XXIII Corp from Paducah, KY up the Ohio River probably to Parkersburg, WV where they transferred to the B&O Railroad to complete their trip to Annapolis, MD. Can you image the sight of 52 steamboats with about 100 yards between vessels? That would be a line of about 4 to 5 miles of boats. Or a continuous line of steamboats passing a single point or mark for 60 minutes.

The str Clara Poe met its end in Tennessee.

The last day for the Clara Poe was on Apr 17, 1865 (Mon). The Clara Poe was burned by the Confederates at Eddyville on the Cumberland River while transporting supplies and barges of hay to Nashville. [12] The war in the west continued for about thirty days after Lee surrendered to Grant on Apr 9, 1865. [13]

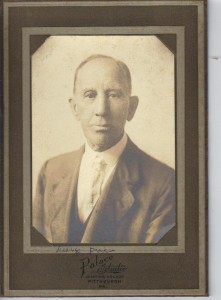

Str Kenton. The str Kenton, owned and operated by Capt George Washington Ebert, had a long and well documented Civil War period of service.

This image is from the collection of the UW La Crosse Murphy Library. It is dated 23 Oct 1861.

Capt Ebert purchased a 1/8 share for $1,150. It is signed by GW Ebert and witnessed by S Peppard who were brothers-in-law in life and business partners for twenty years.

The str Kenton and its crew were chartered for service by the Quartermaster from 27 Dec 1861 to 5 Jan 1862 and from 6 Jan for an unknown duration of time [14]

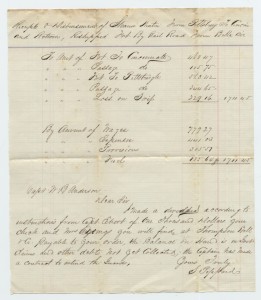

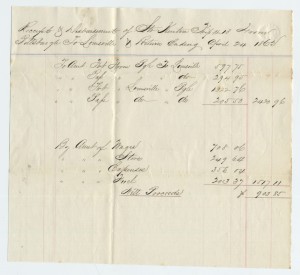

Str Kenton receipts for three round trips between Pittsburgh and Louisville and Pittsburgh and Cincinnati were in the papers of Capt William B Anderson (civilian riverboat captain and pilot). Trip number 13 was dated 24 Apr 1862; trip number 10 was undated but signed by Standish Peppard (partner and first clerk of the str Kenton), and the third receipt was neither dated nor signed. Capt Anderson was quite probably one of the pilots of the str Kentonon these trips. In the Ohio State University Rare Books Collection, his letters to his wife were dated after 24 Apr 1862. He wrote of the str Kenton in the past tense which suggests he had moved to another packet. In the letters, he also expressed his concern about being drafted while between government contracts and paying a $1,000 fine about avoiding the draft. He also wrote about two captains, Capt Adams and the captain of the Florence Miller, arrested for cowardice by General Wright. The Florence Miller was a tinclad packet. The conflict between military and commercial control of the vessels was real.

Receipts and Disbursements of Steamer Kenton Trip #13

From Pittsburgh to Louisville and Return ending April 24, 1862.

Proceeds were $903.85.

From 23 Dec to 31 Jan 1863, Capt Ebert and the Kenton were on the central Mississippi. [15] On Jan 1, 1863, Gen WA Gorman writing to Gen Hurlbut in Memphis states that Capt White informed him that our fleet was “in great need of coal. I send the steamer str Kenton to report to you. [16]

On Jan 12, 1863, the str Kenton was moored near the mouth on the White River according to a personal letter by Lt Cushman K Davis of the 28th Wisconsin Regiment. Approximately 18,000 troops had been transported to the White River from Helena or Napoleon, AR by a fleet of 30 steamers. The str Kenton steamed five difficult miles up the swollen White River on Jan 13. According to Lt Davis, the old General spent most of his time in swearing at the pilot who may have been Capt George W Ebert. On Jan 15 the 28th Wisconsin was visited by a terrific snowstorm. After finding no fight on the White River, the 28th Wisconsin was ordered to Vicksburg for the purpose of another attack. [7]

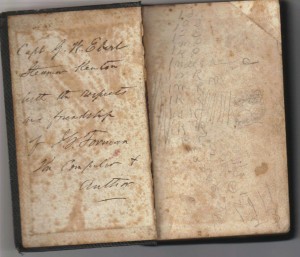

Capt G. W. Ebert

Steamer Kenton

with the respect

and friendship

of J. G. Forman

the compiler &

author

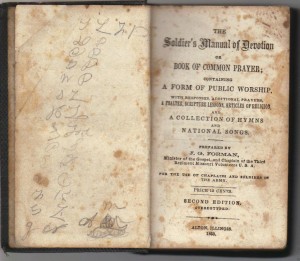

According to the Official Army Registry of the Volunteer Forces of the US Army, Rev JG Forman resigned on May 25, 1863.[9] As chaplain of the Third Regiment of the Missouri Volunteer Infantry (3 year enlistment), he was assigned to the District E Arkansas and participated in the Sherman Yazoo Expedition. [10] Quite possible Rev Forman was aboard the str Kentonin Jan 1863 and befriended Capt Ebert, a Bible reading Methodist from Georgetown, PA.

A soldiers prayer manual gifted to Capt George W Ebert by the chaplain of the 3rd Missouri infantry.

During the war years, Rev JG Forman worked in hospitals and camps where freed slaves, including women and children, were encouraged to go. Rev Forman also made appeals for aid for the “destitute contrabands” in Helena, AR according to an article in the NY Times published Nov 8, 1862. Well known in anti-slavery circles, Louisa May Alcott wrote about his work in “On Race, Sex, and Slavery”. Rev Forman authored works on the contribution of women to the war effort.

In Oct 1863, Capt Ebert and Standish Peppard sold the Kenton to Capt JH Dunlap of Bridgewater, PA. For the duration of the Civil War the packet was in US service. The str Kenton was chartered from 6 Nov 1863 to 18 Mar 1864. On 18 Jan 1864, the “Veteran Seventh” PA Dragoons took passage on the steamer Kenton. We sailed down the Cumberland; passed Clarksville, Fort Donelson, Paducah, places memorable in history; sailed down the Ohio to Cairo, where we arrived on the nineteenth of January. At the same time a steamer arrived from Vicksburg, having on board the Forty-Sixth Illinois Infantry, in command of Colonel Benjamin Dornblaser, also going home on veteran furlough. The colonel spent several hours very pleasantly on the str Kenton, in company with his nephew and several of his former neighbors in the old “Keystone State.” The “Seventh” lay at Cairo two days waiting for transportation. [11]

The Kenton was employed from 26 May to 31 Aug 1864. I have not learned the difference between the term chartered and employed. [12]

The last charter for the str Kenton was 1 Sep to 25 Oct 1864. [13] During that period of time, a grisly encounter occurred. While moored at Eastport on the Tennessee River on Oct 10, 1864, a rebel force attacked from both shores. The Kenton was struck 50 times with shells. Many exploded onboard. One shell exploded in the engine room rupturing a steam line, killing a watchman, and causing general havoc. Capt Dunlap got her away from the landing while the crew extinguished the fire. Those who saw the boat after the attack reported the str Kenton was riddled with shot. The zeal displayed by his crew according to Capt Dunlap was prompted by visions of spending the rest of the war in Libby Prison. [14] Earlier during the month, the Kenton had also been fired into below Clarendon on the White River according to the NY Times archive report dated 4 Oct 1864.[15]

George WE Poe. A short, interesting, historical account of George WE Poe during the Civil War puts the final touches of Georgetown support of the Civil War. George WE Poe ran away from business school in Pittsburgh to join the war effort. His father, Jacob Poe, “was down with the Union boats on the Tennessee River and they had me cooped up in a business school in Pittsburgh. I went down and got aboard the Minerva and come back to Georgetown.” [17]

At age nineteen while learning the river between Pittsburgh and Louisville, George was a cub pilot on the str CT Dumont when she participated in the most exciting event in Parkersburg’s river history. The wharf at the mouth of the Little Kanawha River was filled with some 100 steamboats. All of them with steam up and destined for points all over the Mississippi system. The occasion was the return of the Union soldiers from the Civil War battlefields. The soldiers piled into Parkersburg on B&O trains, marched to the Ohio River, and boarded steamboats. The sidewheeler CT Dumont ferried two crammed loads to Lawrenceburg, IN .[18]

Describing the same event in George Carl Schottenhamel words, “The last great transportation feat was the disbanding of the Union Army in which 233,000 troops, 27,000 horses and mules, and over 2,000 tons of baggage were sent from Washington over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad – a distance of 400 miles. At this point the men and animals were embarked upon a fleet of 92 light draft boats and taken to their destinations in the West.” [19]

“The cost of transporting the troops by water to their destination was $328,208. Moving these men by rail would have cost $746,964, about 2.25 times as much.” [20] During the war, railroads came of age. They became both strategic resources and military targets. After the Civil War , Americans travelled everywhere by train. And it was miserable. Relief was not provided until 1867 when George Pullman marketed his “Palace Cars”.

Summary. Prior to the Civil War, steamboat men from Georgetown were steaming on the Missouri River and other Mississippi tributaries that railroads would not reach for another twenty years. After hostilities commenced, it was soon realized that the rivers, military highways for steamboats, would make or break the Union effort in the western theater of the conflict. Troops and their material, food and supplies were routinely transported by civilian transports contracted and impressed to service. In that effort Georgetown men served their country with distinction. Without their tenacity, without their fearlessness, without their readiness to leave behind the safety of home, how different would the outcome have been? They were the essence of patriotism.

References.

[1] Charles Dana Gibson, “Military Transport, Civilian Crew, During the Civil War“, p4.

[2] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p118.

[3] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p362.

[4] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p362.

[5] Charles Dana Gibson, “Military Transport, Civilian Crew, During the Civil War“, p4.

[6] Charles Dana Gibson, “Military Transport, Civilian Crew, During the Civil War“, p9.

[7] Charles Dana Gibson, “Military Transport, Civilian Crew, During the Civil War“, p9.

[8] Charles Dana Gibson, “Military Transport, Civilian Crew, During the Civil War“, p11.

[9] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p189.

[10] S&D Reflector, Dec 1969.

[11] New York Times Aug 15, 1864.

[12] Frederick Way, Jr.,Way’s Packet Directory, 1848-1994, (Ohio University Press, Athens 1994), p. 99.

[13] Frederick Way, Jr.,Way’s Packet Directory, 1848-1994, (Ohio University Press, Athens 1994), p. 99.

[14] Charles Dana Gibson and E Kay Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels Steam and Sail Employed by the Uniion Army 1861 – 1868, (Ensign Press, Cambridge, MA 1995), p 189.

[15] Charles Dana Gibson and E Kay Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels Steam and Sail Employed by the Uniion Army 1861 – 1868, (Ensign Press, Cambridge, MA 1995), p 189.

[16] Charles Dana Gibson and E Kay Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels Steam and Sail Employed by the Uniion Army 1861 – 1868, (Ensign Press, Cambridge, MA 1995), p 189.

[17] Capt Frederick Way, Jr., Over the Hills to Georgetown, (Waterways Journal) (St Louis, MO, (Nov 30, 1940)).

[18] Capt Frederick Way, Jr., Over the Hills to Georgetown, (Waterways Journal) (St Louis, MO, (Nov 30, 1940)).

[19] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p322.

[20] George Carl Schottenhamel, Lewis Baldwin Parsons and Civil War Transportation, (Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana, 16 Sep 1954), p325.

Copyright © 2012 Francis W Nash

All Rights Reserved